Mickey Carnell on Lady Slipper Orchid Culture 2017

By Lia Andrews. I have had beginner’s luck with many orchids: dendrobiums, cattleyas, phalaenopsis, and even vandaceous orchids, but my two paphiopedilums are barely hanging on. They’re alive but they are not happy, and they certainly have not bloomed. I thought maybe these orchids were not for me. I was surprised to hear Mickey say that when he first started growing orchids, he had immediate success with slipper orchids. He believes that slipper orchids are actually the easiest orchids for those who already have a green thumb with houseplants to start with because their care is not so different.

Slipper orchids are not epiphytes or lithophytes, like most orchids grown in collections like cattleyas and dendrobiums. (Epiphytes get their moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, and occasional debris. Lithophytes grow on rock faces, again without soil.) Slipper orchids are terrestrial and semi-terrestrial plants often found by streams and lakes in most parts of the world. They are in the subfamily Cypripedioideae of orchids. The genera include cypripediums, mexipediums, selenipediums, phragmipediums and paphiopedilums. Most species in this subfamily are endangered in the wild due to habitat loss.

They share some common characteristics. They tend to like their roots wet, but not soggy. They cannot be mericloned, only divided. Seed crosses can vary widely (similar to the variety of genetic variations that can occur when you cross two humans). Their flowers are long lasting.

Water – The biggest take away I got from the presentation was the idea of “hydration” rather than watering. This is a key concept with this group. They need time to soak and fill up. Slippers do not like to fully dry out.

How to Hydrate a Slipper Orchid:

- Get a larger pot with no drainage hole.

- Fill with water and a little food.

- Place your potted slipper inside to soak for at least 15 min – 2 hours.

Water every other day or every 4th day depending on the time of year.

Media – Mickey has grown slippers in all types of media: moss, bark, and various mixes. Just pay attention to moisture and freshness of the media. You will have to adjust watering according to the media. Remember that the more food and water, the faster organic media breaks down. (This is why many growers favor using rocks, sponge rock, etc. in their media to prolong the time before they have to repot). When it does, it becomes acidic and inhospitable to the orchids. The same media can be used for all slippers, the difference is that phragmipediums typically prefer to remain moist, while paphopedilums require a slight drying out between waterings.

Potting – All orchids like a fresh mix. Repot slipper orchids any time you think the media has started to break down to keep the growing media fresh. Like most orchids, they like to be underpotted. Repotting just means replacing the media, it does not necessarily mean going with a larger pot. Like other orchids, slippers prefer to be underpotted. Also, be sure to open the roots a bit so that at least some of the roots are touching the edge of the pot. Slipper roots are a little more delicate than other orchids. Cut away where the roots have become papery. Note: If you have an ailing slipper, cut away dead roots and pot in a tight wad of high quality sphagnum moss. Let the moss dry thoroughly before fully hydrating again.

Note: The wetter the media, the more prone to heat and cold damage.

Food – Mickey prefers high nitrate fertilizer (no urea). A 3:1:2 ratio will grow any plant under the sun. Nitrogen queues the plant to grow. Bloom fertilizer lacks nitrogen and allows the plant to flower. But remember, blooms happen on mature plants.

Pests – Slippers are bothered by few pests aside from occasional mealy bugs.

Cypripedium reginae

CYPRIPEDIUMS

From the Latin Cypris = “Kypris or Aphrodite (Venus)”, Greek Pedilon = “sandal”, thus “Aphrodite’s slipper”.

These are the lady slipper orchids I remember as a kid growing in the forests of upstate New York. They are cold weather orchids widespread in the northern U.S., Canada, Europe, Russia, and China. Mickey did not review their culture in detail as they do not tolerate the heat of the southern U.S. Species include: Cypripedium reginae, formosanum, and gutatum. More pictures of species and hybrids.

Mexipedium xerophyticum

MEXIPEDIUMS

From Mexi = Mexico, Greek Pedilon = “sandal”, thus “Mexican slipper”.

The genera consists of a single species, Mexipedium xerophyticum, found in Oaxaca, Mexico. It grows in limestone crevices.

Selenipedium aequinoctiale

SELENIPEDIUMS

From the Greek Selen = “moon”, Greek Pedilon = “sandal”, thus “moon slipper”.

The natural habitat for the genera is concentrated in the Amazon and thus is at great risk due to deforestation. An attempt was made to use some species as a vanilla substitute, but their difficulty in cultivation made their use inefficient. Species include: Selenipedium aequinoctiale (mimicry orchid), vanillocarpum, and chica.

P. Court Jester

PHRAGMIPEDIUMS

From the Greek Phragma = “division”, Greek Pedilon = “sandal”, thus “divided slipper”.

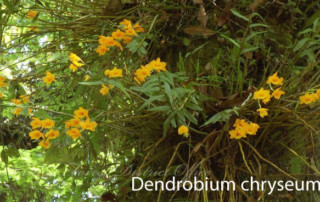

They are native to Latin America and many are endangered in the wild. Species include: Phragmipedium pearcei, besseae, and kovachii and popular hybrids like P. “Sorcerer’s Apprentice”. More pictures of species.

Phragmipediums are known amongst orchid growers as “difficult” plants so I was surprised to hear Mickey say P. Court Jester was the first orchid he ever got to flower. In Mickey’s opinion, phrags are the easiest slipper orchid to bloom. They can bloom sequentially for 6 months to 1 ½ years.

Phrags are very different from paphiopedilums. Of all the slippers, phrags are the most terrestrial. All slippers like their roots “wet but not soggy”, but phrags have the highest tolerance for wetness. You can get away with growing most phrags in standing water. P. bessiae and its hybrids are sensitive to wet feet, but most phrags enjoy being moist all the time. Many growers keep their potted phrags in a saucer of water. Otherwise, you want to check the potting mixture for moisture like you would any potted plant. As soon as it begins to dry out, hydrate the phrag thoroughly; typically every other day or so.

They may not be sensitive to the quantity but they are picky on quality. Every successful phrag grower I have spoken to swears that rain water is the secret. Their famous sensitivity to water quality is likely due to their dependence on mycorrhizal fungi (which perish in the chemical-laden water supply most of us have access to). This is the opinion of expert phragmipedium grower, Gary Murza.

Paph. (Via Victoria x Spring Free) x spicerianum grown by Barb Murza

PAPHIOPEDILUMS

From Paphos = a city in Cyprus, a place sacred to Aphrodite (Venus), Greek Pedilon = “sandal”, thus “Venus slipper”.

These are native to Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Paphiopedilums are widely hybridized and common in orchid collections. Many adapt well to the southern U.S. The bulk of Mickey’s talk focused on this genera. He brought in examples of each subgenus for us to see and touch.

General Culture:

Media – 2 parts coconut or bark : 1 part charcoal : 1 part perlite. Mickey does not like lava rock because they accumulate salts. Paphs and phrags can be grown in the same media. Paphs really don’t like acid media. Be sure to repot when the media begins to break down.

Water – Never let them dry out completely. Use room temperature water. Do not use softened water. Potting media should stay moist but not wet. Most paphs like to be watered every other day. Paphs do not like water on their leaves (in South Florida. In California you would not need to worry about this). If you get water on their leaf axis it can easily cause fungus and rot. To remedy this you can grow in moss to limit the frequency of watering and/or hydrate them by soaking just the roots in water rather than spraying with a hose or watering from overhead.

Food – Paphs like to eat frequently. You can feed a dilute amount at every watering. Simply add a little food to the water and allow roots to soak. Flush with plain water every 4th watering. Alternately, feed weakly weekly, flushing with plain water 4-6 weeks.

Light – 800-1,000 foot candles. 70% shade (shadow east – too much light). Leaves should feel cool to the touch. Most paphs like early morning sun, though they thrive in all day filtered light. If they are in a place where the phalaenopsis have dark green leaves, it is too shady. As with all plants, the higher the light exposure, the more food and water required for the plant to keep up.

Humidity – 70% humidity is ideal. Use a humidity tray, fine mist several times a day, or use a humidifier.

Temperature range – 55°-85° is the ideal temperature range for most paphs.

Air Movement – moist, vigorous air movement reduces chance of disease.

New growth on a healthy plant will mature and bloom within 9 months.

At tonight’s meeting, the winning orchid was Paph. (Via Victoria x Spring Free) x spicerianum, expertly grown by Barb Murza. Barb says this Paph. spicerianum crosses are reliable bloomers and easy to grow.

Subgenus: Barbatum/Sigmatopetalum

Species include: Paph. venustum, wardii, purpuratum, argus, appletonianum,barbatum, callosum, lawrenceanum, mastersianum, sukhakulii, superbiens, venustum, viniferum and wolterianum.

Widespread through Southern China, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Known as maudiae-type paphs due to their mottled leaves. Warm monsoon (monsoon summer/dry cool winter) growers ideally suited to South Florida. Prefer shade (500-1500 foot-candles).

Subgenus: Paphiopedilum/Insigne

Species include: Paph. coccineum, hirsutissimum, spicerianum, barbigerum. boxalii, charlesworthii, druryi, exul, fairrieanum, gratrixianum, helenae, henryanum, herman, insigne, and trigrinum.

Native to Southen China, Bhutan, Laos, Burma, and Thailand. Most are cool monsoon growers (require cooler autumn temperatures to bloom). Distinguished by green, strap-shaped leaves. Bloom in winter. Prefer bright light (high phalaenopsis, low cattleya light).

Subgenus: Brachypetalum

Species include: Paph. bellatulum, longipetalum, niveum, bellatulum, concolor, godefroyae, xgreyi, niveum and thaianum.

Native to tropical China, Vietnam, Burma, Laos, and Thailand. Distinguished by their tessellated and succulent, water-filled leaves. They do not need as much water as other paphs. According to Mickey they come to flower quickly. They like more food and particularly do not like water on their leaf axis. These slippers can tolerate temperatures into the 40’s. They enjoy the monsoon summer/dry cool winter seasons of South Florida. Cool dry winter + calcium supplements for summer blooming. Shade. Good air movement.

Subgenus: Parvisepalum

Species include: Paph. armeniacum, delenatii, malipoense, micranthum, vietnamense, emersonii, hangianum, jackii, and malipoense.

Native to tropical China and Vietnam. They are distinguished by tessellated thin leaves and flowers with large, inflated pouches. Cool dry winter + calcium supplements for summer blooming. Shade. Good air movement.

Strap-Leaf Multiflorals – Distinguished by their ability to sustain multiple blooms. They like good air flow. Must have a 6-8 week cool period (50-60°F) to bloom. Mickey considers them difficult to kill and they are fast growers. The leaves should be an apple green color for optimal flowering. This subgroup prefers more light; most tolerating cattleya-level light (2000-3000 ft-candles). They prefer to grow warmer and shouldn’t be exposed to temperatures below 50°-55°. They enjoy the monsoon summer/dry winter seasons of South Florida.

Subgenus: Cochlopetalum

Species include: Paph. glaucophyllum, liemianum, moquetteanum, primulinum, victoria-mariae and victoria-regina (syn. chamberlainianum).

Native to Indonesia. Sequential bloomer. Mickey states that cochlopetalums are great for growers in Southwest Florida. Again, they are warm weather monsoon growers.

Subgenus: Coryopetalum

Species include: Paph. adductum, gigantifolium, intaniae, kolopakingii, ooii, philippinense, platyphyllum, praestans (syn. glanduliferum), randsii, rothschildianum, sanderianum, stonei and supardii.

Simultaneous bloomer.

Subgenus: Pardalopetalum/Polyantha

Species include: Paph. parishii, stonei, lowii, dianthum, haynaldianum, lynniae, and richardianum.

Primarily found in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea. Simultaneous bloomer. These enjoy cooler, drier weather.

DO PAPHIOPEDILUMS LIKE LIME?

For a mixed collection use: balanced fertilizer, 40ppm calcium, 20-30ppm magnesium, and pH 6.2-6.6.

For Calcareous Species add a top dressing of crushed oyster shell, pelletized limestone, or dolomitic limestone chunks.

Calcareous Species include: armeniacum, malipoense, microanthum, emersonii, bellatulum, concolor, godefroyae, niveum, philippinense, sanderianum, stonei, glanduliferum, wilhelminae, supardii, dianthum, glaucophyllum, liemianum, primulinium, Victoria-regime, hirsuitissmum, charlesworthii, insigne, barbigerum, exul, spicerianum, fairrieanum.

MISCELLANEOUS ORCHID TIPS

- Oncidiums growing too dark in winter won’t bloom in Spring. This is why many growers can only get their oncidiums to bloom once a year in the Fall.

- Ring stakes allow light to hit new growth and increase blooming in cattleyas.

- Bare root orchids love to be watered daily, and by watered Mickey means fully hydrated of course, to mimic the nearly constant misting many of them receive in their natural habitats. Professional growers typically mist their bare root orchids for 45 min twice daily and feed twice a week. Hobbyists can set up a sprinkler on a timer for a similar effect. For those of us with other responsibilities Mickey recommends at least once a week fully hydrating your orchids, either soaking in water or watering them 3 times a day (breakfast, lunch, and dinner). This particularly applies to vandas. Palm tree vandas are food and water-deprived vandas.

REFERENCE

Blue Pagoda

http://slipperorchids.info/paphdatasheets/parvisepalum/

https://personal.uwaterloo.ca/jerry/orchids/cnotes/paph2.html

http://www.cloudsorchids.com/culture/slippers.htm

http://slipperorchids.info/paphspecies/index.html

https://www.lookingafterorchids.com/useful-articles/lady-slipper-orchid-care/

http://www.slippertalk.com/forum/showthread.php?t=27013